Following talks by Dr Bryan Sitch and Dr Campbell Price (see part 1) the conference provided curator-led tours of the Ancient Worlds galleries and an opportunity for the delegates to feed back on their experience of viewing human remains within a museum context. This group discussion generated a wide-range of questions and responses, demonstrating the complexity and necessity of such an open debate.

Much of this discussion focused on the ethics of display and the ways in which museums try to re-humanise human remains, taking into consideration the objectifying effect of the museum display case and the difficult subject-object duality of the material dead. Approaches such as referring to the deceased by name, wherever possible, and using ‘he’ or ‘she’ in interpretation were highlighted as a means of showing respect and sensitivity to the deceased. Visual interpretive methods such as facial reconstructions were also discussed, although it was felt that these methods can be distracting and/or misleading in some contexts. All agreed that context is key when it comes to display – providing a rich socio-cultural and/or scientific context allows a greater understanding of the person.

Dr Price explained how many of these approaches had been incorporated into the Ancient Worlds gallery which opened in 2012. The display of human remains within this gallery had been based upon a series of experimental phases of display, which included different ways of covering the body, this approach generated discussion amongst museum visitors and professionals, and enabled audience consultation for the re-display. As a result, Asru, an Egyptian woman from the 25th-26th dynasty whose preserved body is on display in the gallery, is covered from collar to ankle with ancient linen and has been re-situated within her coffin. As she is displayed beneath visitor’s eye-level, with the coffin lid hovering over her body, visitors are able to choose whether or not to view the human remains, and soft, motion sensor lights ensure her display is subtle. Scientific context has also been built with interviews and research from the KNH Centre for Biomedical Egyptology.

It was felt that there is an overall lack of consensus on how to display human remains and that matters of display and reception are very much dependant on the type of museum and collection. The example of medical museums was presented in which human remains tend to be considered more as specimens than people and the group questioned whether this was a consequence of encountering a fragment rather than the whole. Similarly, the group considered the factor of time and its impact upon reception. For example, there seems to be a difference in how we view the long dead in comparison to the recently dead which feeds into our museum experience – ancient remains often feel more distant from us and therefore seem less likely to evoke an emotional response and more likely to generate curiosity.

What I found particularly fascinating in this discussion was the strong local connection that many felt for the Egyptian mummies. Many delegates recounted stories of visiting them in their childhood, referring to them as ‘old friends’ and describing the sense of loss they felt when some were taken off of display to allow for a greater material culture context in the new Ancient Worlds gallery. It would be fascinating to investigate this, and other similar localised relationships, further and find out how unique this heightened attachment is to ancient Egyptian collections and the specific values we assign them.

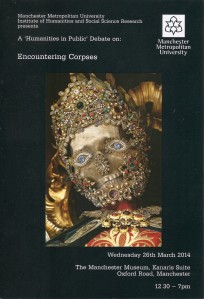

Above all Encountering Corpses demonstrated the importance of discussing the display and reception of human remains within an inter-disciplinary context. The way we view and understand human remains in a museum setting is informed by our prior-knowledge and experiences and has, therefore, always been framed by the many different social, cultural, medical and artistic encounters we have experienced both individually and within our cultural memory. The fact that this conference sold out six months in advance is testament to its current relevance across the humanities and social sciences. Hopefully such collaborations will lead to a more inclusive, balanced and ethical approach, not just to matters of display and reception but to wider issues relating to the care, management, conservation, research and storage of human remains within museums.